Big Tobacco Tactics

In the 1950’s the tobacco industry was faced with a huge threat: a number of scientific studies had been published linking smoking with lung cancer. Big Tobacco had to move quickly to protect profits. There is a growing body of literature that points to the role of vested interests as barriers to the implementation of public health policies. The best known of this literature concerns the tobacco industry and its efforts to undermine public health efforts to reduce smoking. The US Master Settlement Agreement has allowed researchers to access internal tobacco industry documents which have been invaluable in demonstrating strategies employed by tobacco companies over more than 50 years to counter and undermine policies that might adversely affect their interests

What can we learn from Big Tobacco?

Front Groups, ‘Astro-Turfing’ and SAPROs

Front groups are organisations that appear to be independent – but these groups are actually controlled by a hidden parent group and are set up purely to serve the interests of this group

‘Astro-turfing’ is the name given to the establishment of fake grassroots groups.

Social Aspects/Public Relations Organisation (aka: SAPRO) are established by industries like Big Tobacco to divert attention away from evidence based public health policies that may affect profit margins and towards benign interventions that do not pose a threat to profit margins.

Derek Yach states that Phillip Morris genuinely aims for a smoke-free world by contributing to the 'Foundation for a Smoke-Free world' (see here). The World Heart Federation; however, alongside the Global Coalition for Circulatory Health has condemned the launch of the foundation, which is a vehicle for the tobacco industry (see here) and another commentary here and an editorial here.

The National Smokers Alliance is a prime example of this tactic. The National Smokers Alliance was founded and funded by Phillip Morris Tobacco Company but their involvement was hidden behind the appearance of this group as a grassroots organisation that opposed the introduction of smoke-free laws in the 1990's.

Australian examples of "Astro-turfing." The AAR provides testimony from retailers and members of the public, though the site is funded by international tobacco companies.

Casting Doubt Over Science

In a now infamous memo a tobacco executive said, "Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the 'body of fact' that exists in the minds of the general public. It is also the means of establishing a controversy."

Commissioning Research and Publications

The tobacco industry has a long history of commissioning research with the intent to undermine scientific consensus thereby creating doubt or confusion in the general public about the health impact of smoking.

By commissioning research the tobacco industry has also bought credible allies from within the scientific community.

Hiring Industry-Friendly "Independent Experts"

The tobacco industry relies on industry-friendly 'experts' who are critical of control and regulation and are paid to publicly testify in favour of industry.

Selective About Evidence

The tobacco industry is known to 'cherry-pick' evidence. This is where the industry selects data that aligns with their position, while ignoring data that may contradict that position. They may rely on one or a small number of studies that go against the consensus scientific view.

Financial Incentives for Researchers

The tobacco industry financially incentivises the opinions of researchers by paying or sponsoring them. This includes honoraria for speaking, paid travel, and other perks.

Undermining credibility of independent experts, and marking peer reviewed research as 'junk science'

The tobacco industry have a proven history of undermining the credibility of experts and claiming peer reviewed research as 'junk science' in an attempt to create doubt around science that supported claims that their products caused harm see (Samet & Burke, 2001) and (Bero, 2013).

DIRECT LOBBYING REFERS TO CONTACT BETWEEN THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY AND POLICYMAKERS. THE AIM OF THIS CONTACT IS TO FORM OR MAINTAIN BONDS BETWEEN TOBACCO AND GOVERNMENT SO THAT INDUSTRY CAN INFLUENCE THE DEVELOPMENT OF NEW REGULATION OR CALL INTO QUESTION EXISTING LEGISLATION

Wining and Dining

Another form of direct lobbying is the provision of hospitality or giving of gifts to those responsible for legislation and regulation. This also includes providing funds to political campaigns.

Indirect Lobbying

Indirect lobbying is similar to direct lobbying except that in the case of indirect lobbying Big Tobacco employs people or organisations to lobby on their behalf see here.

Direct and Indirect Lobbying

THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY CONFUSES DEBATES ABOUT INCREASES IN TAX ON TOBACCO PRODUCTS WITH BROADER TAX DEBATES SO THAT PEOPLE OPPOSE THE TAX INCREASE ON TOBACCO PRODUCTS

The tobacco industry limits the possibility of tax increases by increasing prices & increasing prices and disguising these as tax increases.

The tobacco industry also encourages groups supportive of higher taxes to push for alternative taxes.

Tax Arguments and Actions

MOUNTING CHALLENGES ON A LEGAL BASIS HAS BEEN A CONSISTENT TACTIC OF THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY

For example the legal challenge to the plain packaging laws. The tobacco industry challenged the introduction of plain packaging laws on tobacco products in Australia by using copyright and fair trade legal arguments for examples see here; however, Australia won the legal battle.

In 1998 several states in the United States sued major tobacco companies, which lead to what has been termed the ‘master settlement agreement’. It is from documents subpoenaed during this trial that the tobacco companies’ tactics were exposed see here.

Legal and Official Challenges

RIVAL TOBACCO COMPANIES BAND TOGETHER TO PROMOTE INDUSTRY FRIENDLY OUTCOMES IN VARIOUS SPHERES

Proposing Alternative Legislation

Tobacco companies have particularly promoting voluntary and self-regulation strategies

Create controversy, frame as an individual rights or business owner rights issue. NANNY STATE

“There are many examples of common sense health and safety measures that regulate the use of legal products when certain uses could harm workers and the general public.”

Using industry employees/staff as lobbyists

Calling for an end to public service announcements about the health impacts in order to not "bias the debate"

Intelligence Gathering

The tobacco industry monitors and gathers information about their opponents and social trends in order for them to anticipate challenges to their economic interests that may arise in the future.

Company Collaborations

Like other large industries, the tobacco industry has considerable legal and economic power. the industry uses this power imbalance to frighten their opponents.

There has been intimidation and interference particularly in developing nations like Kenya where British American Tobacco have 70% of the market share see here. The tobacco industry's intimidation tactics include using their wealth and legal resources to intimidate individuals and local government bodies (see Sweda & Daynard, 1996)

Intimidation

In 1953 the CEOs of the united states' biggest tobacco companies met with one of the biggest public relations companies- Hills and Knowlton. This marked the beginning of a widespread public relations campaign to convince the public that smoking was not dangerous.

Since this time the tobacco industry has continued to utilise the media and public relations managers to encourage opposition to various changes in regulations, legislation or taxes.

Plain Packaging

There have been many tactics used by the tobacco industry in an attempt to stop plain packaging legislation from being introduced see (Chapman & Carter, 2003). Australia is the first country to introduce plain packaging laws but it took many years for it to come to fruition (see here for a timeline and industry arguments used in an attempt to prevent plain packaging laws coming into effect).

Arguments against plain packaging have been prominent on industry websites. For example:

Media and Publicity Campaigns

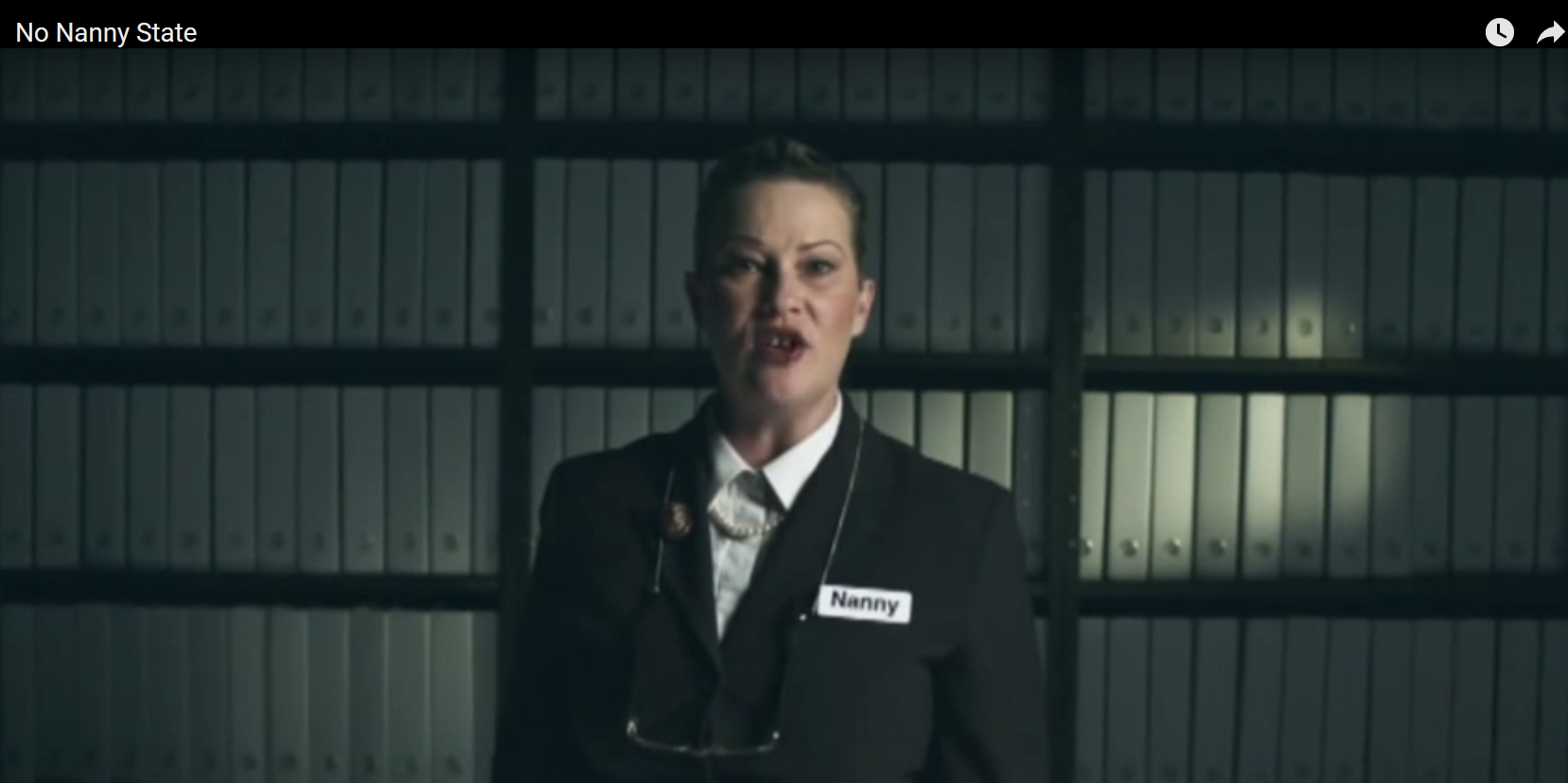

Television advertisement run by Imperial Tobacco in response to the introduction of plain packaging legislation

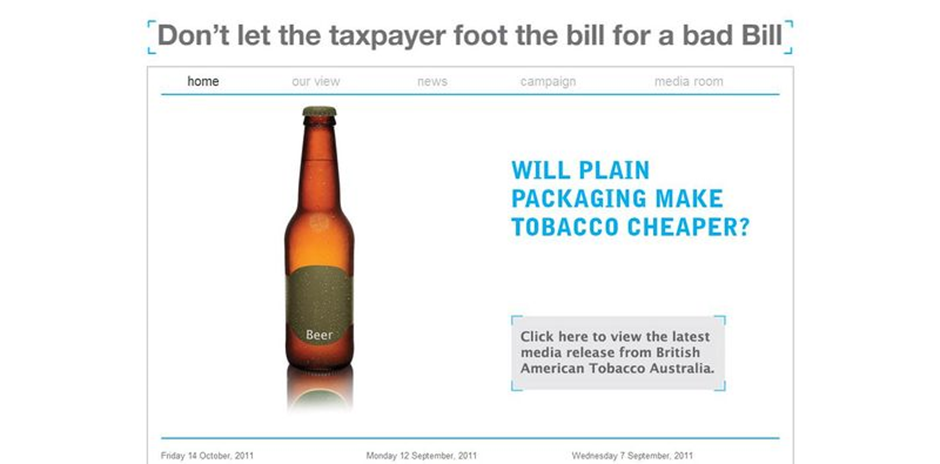

Online advertisement run by British American Tobacco in response to the introduction of plain packaging legislation

The Australian Association of Convenience Stores (AACS) was an organisation set up to represent 'local shops'. British American Tobacco (BAT), Imperial Tobacco Australia (ITA) and Phillip Morris Limited (PML) invested funds in the AACS campaign against plain packagaing. The ITA gave more than $1 million. BATA chipped in $2.2 million and PML $2.1 million see here.

The tobacco industry works to shift the focus of the argument away from health issues. trying to shift the policy/public focus, claiming that other issues are more important.

Harm reduction

The tobacco industry claim involvement in harm reduction strategies in order to reduce the damage caused by their product. By promoting these efforts the tobacco industry attempts to create an image of the good corporate citizen.

Low tar cigarettes

One example of harm reduction tactics was the proliferation and labeling of cigarettes as ‘low tar’ from 1989 onwards. The practice was discontinued in 2006 because the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission found that the use of ‘light’ and ‘mild’ on cigarettes was misleading to consumers. The practice was introduced because it was originally thought that making consumers aware of the tar content would lead them to switch to cigarettes thus reducing harm and potentially lead them to quit smoking altogether. The evidence showed; however, that reduced tar cigarettes was not leading to people quitting smoking but were in fact diverting them from the attempt with the illusion of reduced harm cigarettes.

Example of tar content labeling on cigarettes here.

E-cigarettes

E-cigarettes are the latest ‘harm reduction’ gambit with the tobacco industry suggesting that they are a safer alternative to cigarettes and are another way of helping smokers quit. This is despite their original opposition to e-cigarettes (whom they saw as competition) but they now see as a new way of increasing profit. E-cigarettes are battery operated devices that deliver nicotine to the consumer. The retail sale of e-cigarettes containing nicotine is banned in Australia. They have not been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration of Australia.

There is a community of e-cigarette users called ‘vapers’ who have thrown their support behind the legalising of e-cigarettes, here and overseas. They profess not to be aligned with big tobacco see here but as big tobacco continue to buy up small e-cigarette companies it is inevitable that they are fighting the fight of big tobacco who have in the past use grassroots action to push their agenda.

Research released in 2011 suggested that e-cigarettes led to the cessation of smoking; however, it is interesting to note that the research was funded by a large multinational tobacco company, Philip Morris International who have bought into the e-cigarette industry see here. Questions need to be asked about research funded by industry with economical vested interest in the outcomes see a commentary here on 'the conversation'. However, it has also been shown that overseas (e.g. the United Kingdom) where e-cigarettes are legal that the vast majority of people who are using e-cigarettes are also smoking see [Drummond & Upson, 2014].

The Cancer Council Australia also has a position on the value of e-cigarettes, which is contrary to the industry stance. The biggest successes in reducing smoking rates are taxing see [Scollo et al, 2003] and [Wilson et al, 2012] smoking bans see [White et al, 2011], health warnings on packets see [Strahan et al, 2002] , and potentially plain packet laws see [Freeman, Chapman & Rimmer, 2012] and [Wakefield, Hayes & Durkin, 2013]. While these legislative actions are known to reduce smoking rates the jury is still out with harm reduction strategies like e-cigarettes.

Neuro-ethics argument

There are ways to influence research in order to divert attention from the industry’s responsibility of the harm tobacco causes its consumers. The neuro ethics argument is an example of this. The neuro ethics argument puts the responsibility of the damage done by products such as tobacco that causes harm to its consumers onto the individual highlighting the biomedical role (e.g. genetics) see [Miller, Carter & De Groot, 2012].

By investing heavily in research that concentrated on looking at the effect of the biomedical aspect of tobacco harm the tobacco industry was attempting to divert attention away from forms of tobacco control that would impact on their profit (plain packaging, health warnings etc.). Tobacco industry documents that were released make it plain that while the industry was fighting to deny the evidence that nicotine was addictive, it was investing millions in genetic research on nicotine dependence see [Miller, Carter & De Groot, 2012].

Black market

Tobacco companies often claim that actions such as tax increases, plain packaging and health warnings on packaging will lead to an increased illegal tobacco trade.

The Cancer council have critiqued the tobacco industry claims here.

Diversion Tactics

the Tobacco industry has a long history of influencing public policy through the development or promotion of non-regulatory initiatives and voluntary codes.

Developing and promoting nonregulatory initiatives

The tobacco industry have often recommend policies (e.g. education) that are proven to be ineffective, particularly when regulatory measures are being proposed. These measures on their own, have limited effectiveness [Coombes, Bond, Van & Daube, 2011]. Particularly when it comes to anti-smoking education to young people see [Biener 2000] and [Pechmann & Reibling, 2006].

Developing and promoting voluntary codes and self-regulation

The tobacco industry has a long history of developing and promoting voluntary codes and self-regulation in Australia. For example, Philip Morris introduced their own system of placing health warnings on their cigarette packaging; however these were ineffective and merely a way of them avoiding more effective government legislation of health warnings. These self-regulation initiatives are currently being pursued in the developing world where regulation is weak or not in place. Internal documents show that Philip Morris were deliberate in seeming to responds to public health concerns when in fact they were doing so in an ineffective way. By doing this they also had the secondary outcome of looking like they were socially responsible see [Wander & Malone, 2006].

Within Australia regulation was voluntary created from deals struck with government. The way the tobacco companies flouted these self-regulation is well documented see [Chapman, 1980] and [Carter, 2003].

Developing new regulation and planning implementation

With increasing legislation occurring in countries such as Australia, the UK and the US, tobacco companies are looking to developing nations like Africa to retain their profit margins. The tobacco market grew by 70% throughout the 90s through to the 21st century see. The tobacco industry has been reported as having developed a suite of national policies which were then promoted to governments in developing countries. They have also used the economic reliance on tobacco growing and exportation in developing nations as leverage to avoid legislation on tobacco use in developing nations see [Otanez, Mamudu & Glantz, 2009].